The Mediterranean Diet (MedDiet) is one of the world’s most important and well-researched eating patterns. It’s more than just a healthy way of eating – it’s so special that in 2010, UNESCO named it an important part of humanity’s intangible cultural heritage. This recognition shows that it’s not just a collection of healthy foods but a cultural archetype encompassing food selection, processing, and distribution methods (Dominguez, 2021).

What is the Mediterranean Diet?

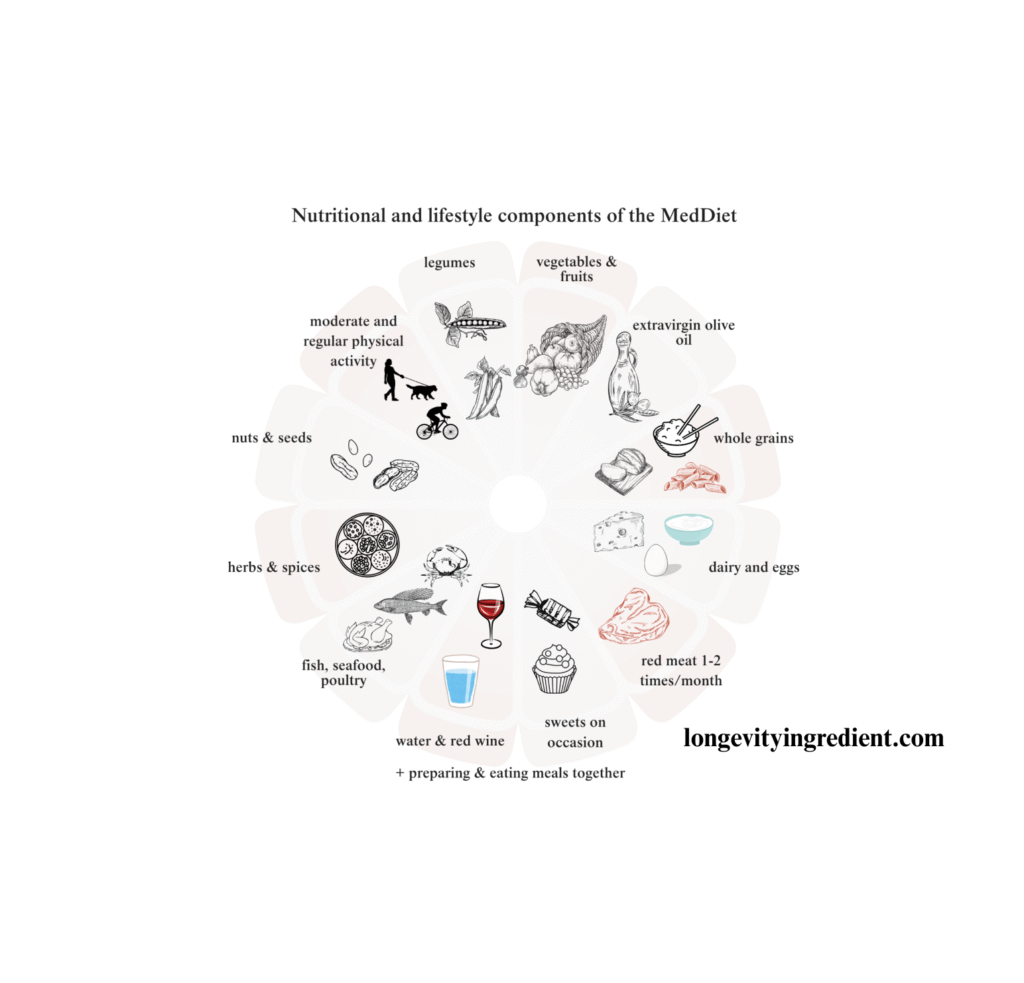

The Mediterranean Diet combines health and pleasure. Fresh vegetables and fruits are at its heart, complemented by wholesome grains and protein-rich legumes. The star of the show is extra virgin olive oil, lending its golden touch to both cooking and seasoning.

This diet celebrates the bounty of the sea with regular servings of fish and seafood while treating meat as an occasional treat rather than a daily necessity. Dairy appears in modest portions, mainly as yoghurt and carefully selected cheeses. Nature’s candy – fresh fruit – takes centre stage for dessert, making sugary treats a rare indulgence.

But the Mediterranean lifestyle extends beyond the plate. It’s about savouring each moment: cooking with aromatic herbs and spices, sharing meals with loved ones, and embracing the rhythm of life through daily physical activity. Even rest is elevated to an art form, with the traditional siesta offering a peaceful midday pause.

This approach to eating and living emphasizes a deep connection with nature, favouring locally sourced, minimally processed foods. Wine, when consumed, is treated not as a mere beverage but as part of the meal’s social fabric, enjoyed in moderation and always alongside food. (Dominguez, 2021).

In academic settings, baseline adherence to the Mediterranean diet can be measured by the MEDAS (Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener), which is a 14-point scoring system. This screener includes specific criteria for scoring points based on various dietary habits.

This particular screener comes from the publication of Schroder et al., 2011.

| MEDAS (Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener) | Criteria for 1 point |

|---|---|

| Do you use olive oil as the principal source of fat for cooking? | Yes |

| How much olive oil do you consume per day (including that used in frying, salads, meals eaten away from home, etc.)? | ≥4 tablespoons |

| How many servings of vegetables do you consume per day? Count garnish and side servings as 1/2 point; a full serving is 200 g. | ≥2 |

| How many pieces of fruit (including fresh-squeezed juice) do you consume per day? | ≥3 |

| How many servings of red meat, hamburger, or sausages do you consume per day? A full serving is 100–150 g. | <1 |

| How many servings (12 g) of butter, margarine, or cream do you consume per day? | <1 |

| How many carbonated and/or sugar-sweetened beverages do you consume per day? | <1 |

| Do you drink wine? How much do you consume per week? | ≥7 cups |

| How many servings (150 g) of pulses do you consume per week? | ≥3 |

| How many servings of fish/seafood do you consume per week? (100–150 g of fish, 4–5 pieces or 200 g of seafood) | ≥3 |

| How many times do you consume commercial (not homemade) pastry such as cookies or cake per week? | <2 |

| How many times do you consume nuts per week? (1 serving = 30 g) | ≥3 |

| Do you prefer to eat chicken, turkey or rabbit instead of beef, pork, hamburgers, or sausages? | Yes |

| How many times per week do you consume boiled vegetables, pasta, rice, or other dishes with a sauce of tomato, garlic, onion, or leeks sauted in olive oil (so called “soffrrito”)? | ≥2 |

MEDAS scores range from 0-14 points total. The scores indicate different levels of Mediterranean Diet adherence: scores of 5 or less show low adherence, scores between 6-9 show moderate adherence, and scores of 10 or higher show strong adherence (García-Conesa 2020).

Mechanisms Behind the Benefits

One key mechanism explaining the MedDiet’s benefits involves the gut microbiota, which has emerged as a crucial player in the diet-health relationship through metabolites derived from microbial fermentation of nutrients, particularly short-chain fatty acids (Dominguez, 2021).

Research shows that looking at specific nutrients helps us understand healthy diets.

Dark-colored vegetables and fruits contain powerful anti-inflammatory and antioxidant compounds. These compounds appear in many different diets and may help explain why certain foods promote better health as we age (Hsiao & Chen 2022).

Polyphenols play a significant role in the diet’s effectiveness. In a Mediterranean cohort from Catania, Italy, the mean polyphenol intake was high (663.7 mg/d), with major sources including nuts, tea, coffee, fruits (especially cherries and citrus), vegetables (particularly artichokes and olives), chocolate, red wine, and pasta. Additionally, the PREDIMED trial demonstrated that a high intake of total polyphenols, especially stilbenes and lignans, was associated with reduced mortality risk. The distinguishing factor in PREDIMED participants was their consumption of polyphenols from olives and olive oil (Dominguez, 2021).

Impact on Mortality & Biological Ageing

Research consistently shows that increased adherence to the Mediterranean Diet pattern correlates with reduced total and cause-specific mortality. A comprehensive meta-analysis of 29 prospective observational studies, involving over 1.67 million participants, revealed a 10% reduction in all-cause mortality for every two-point increase in MedDiet adherence. The effect was even stronger among Mediterranean residents compared to non-Mediterranean populations (hazard ratios of 0.82 and 0.92, respectively) (Barber, 2023).

The diet’s impact on longevity is supported by biological evidence. Studies have shown that adherence to the Mediterranean Diet is associated with longer telomere length, suggesting it may also slow the biological ageing process (Barber, 2023).

Blue Zones: A Global Perspective on Longevity

The Blue Zones, areas with unusually high concentrations of centenarians, provide valuable insights into dietary patterns and longevity. These regions include Okinawa (Japan), Ikaria (Greece), parts of Sardinia (Italy), and the Nicoya Peninsula (Costa Rica) (Pes, 2022).

Dan Buettner, a National Geographic journalist, is credited with the concept of Blue Zones. In addition to the four locations mentioned above, a fifth one has been established: Loma Linda, California (United States of America) (Tan 2024).

These populations have been rigorously validated through death certificates and social security records. Interestingly, the dietary patterns across Blue Zones show remarkable diversity. Even within Mediterranean Blue Zones, there are significant deviations from the classical Mediterranean Diet (Pes, 2022).

Beyond Diet: A Complex Picture

The relationship between diet and longevity is more complex than often portrayed. In Sardinia’s Blue Zone, for example, potentially negative effects of a diet high in saturated fats and potato-derived starch were likely offset by the intense daily physical activity of their pastoral lifestyle. Additionally, genetic factors present in Blue Zone populations may have diminished the relative importance of diet in their exceptional longevity (Pes, 2022).

Recent research suggests that hybrid approaches might be beneficial. For instance, the Mediterranean-styled Japanese diet combines elements from both traditions, focusing on vegetables, beans, and fish while incorporating specific elements from both cultures. This fusion demonstrates how different healthy eating patterns can be adapted and combined (Santa, 2022).

Why the Mediterranean Diet Isn’t the Ultimate Protocol

While the Mediterranean Diet has proven benefits, calling it the “ultimate” longevity protocol would be an oversimplification. The evidence from Blue Zones shows that different dietary patterns can promote longevity when adapted to local contexts and individual needs. The success of any dietary pattern depends heavily on its interaction with lifestyle factors, genetics, and environmental conditions (Pes, 2022).

Furthermore, research on the transferability and effectiveness of the Mediterranean Diet in non-Mediterranean populations requires further investigation (Dominguez, 2021). What works in one population or region may not work equally well in another.

Conclusion: A Holistic Approach to Longevity

Medicine should aim not merely at life’s prolongation but at promoting old age while avoiding multimorbidity and disability as much as possible (Dominguez, 2021). The Mediterranean Diet can certainly be an excellent longevity protocol, but it’s just one component of a complex system that influences healthy ageing.

The key to understanding longevity lies in recognizing that dietary patterns are largely affected by culture, ethnicity, geographical locations, and cooking methods. As we continue to explore the fascinating field of longevity, we must consider diet as part of a broader lifestyle approach that includes physical activity, genetic factors, and various other elements that contribute to a long, healthy life.

Reference

Impact of Mediterranean Diet on Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases and Longevity (Dominguez et al., 2021) doi: 10.3390/nu13062028

A Short Screener Is Valid for Assessing Mediterranean Diet Adherence among Older Spanish Men and Women (Schroder et al., 2011) doi: 10.3945/jn.110.135566

Exploring the Validity of the 14-Item Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS): A Cross-National Study in Seven European Countries around the Mediterranean Region (García-Conesa et al., 2020) doi: 10.3390/nu12102960

What constitutes healthy diet in healthy longevity (Hsiao & Chen 2022) doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2022.104761

The Effects of the Mediterranean Diet on Health and Gut Microbiota (Barber et al., 2023) doi: 10.3390/nu15092150

The Recommendation of the Mediterranean-styled Japanese Diet for Healthy Longevity (Santa et al., 2022) doi: 10.2174/0118715303280097240130072031

Diet and longevity in the Blue Zones: A set-and-forget issue? (Pes et al., 2022) doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2022.06.004

Navigating the Healthcare Conundrum: Leadership Perspective from a Premier Healthcare Organization in Loma Linda’s Blue Zone (Tan et al., 2024) doi: 10.2147/JHL.S452188

[…] Is the Mediterranean Diet an Ultimate Longevity Protocol?By Agata RzeszótkoThe Mediterranean Diet (MedDiet) is one of the world's most important and well-researched eating patterns. It's more than just a healthy way of eating -… Leave a Comment […]