Bone strength and muscle health are essential for longevity

Loss of bone and muscle with age poses a serious threat to independence in later life.

Osteoporosis is a major public health problem due to its link with fragility fractures, primarily of the hip, spine, and distal forearm.

Sarcopenia, on the other hand, is the age-related loss of muscle mass and function, which may increase fracture risk by raising the likelihood of falls. In muscle ageing, it’s important to remember that declining muscle mass is not the only factor affecting muscle function. Other aspects of muscle quality also play a role, including, among others: muscle composition, aerobic capacity and metabolism (Curtis et al., 2015).

Muscle Strength as a Health Indicator

The “Global consensus on optimal exercise recommendations for enhancing healthy longevity in older adults” highlights how aerobic capacity and muscle strength are interconnected and together influence mortality risk (Izquierdo et al., 2025). Remarkably, individuals over 60 in the lowest third for strength were 50% more likely to die from all causes than those in the upper third (McLeod et al., 2016).

Higher levels of self-reported physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness, and muscle strength all predict better survival (Izquierdo et al., 2025). This underscores the importance of muscle size and strength for longevity and health, giving new meaning to Darwin’s “Survival of the Fittest” – the strongest and fittest individuals are indeed more likely to live longer, healthier lives (McLeod et al., 2016).

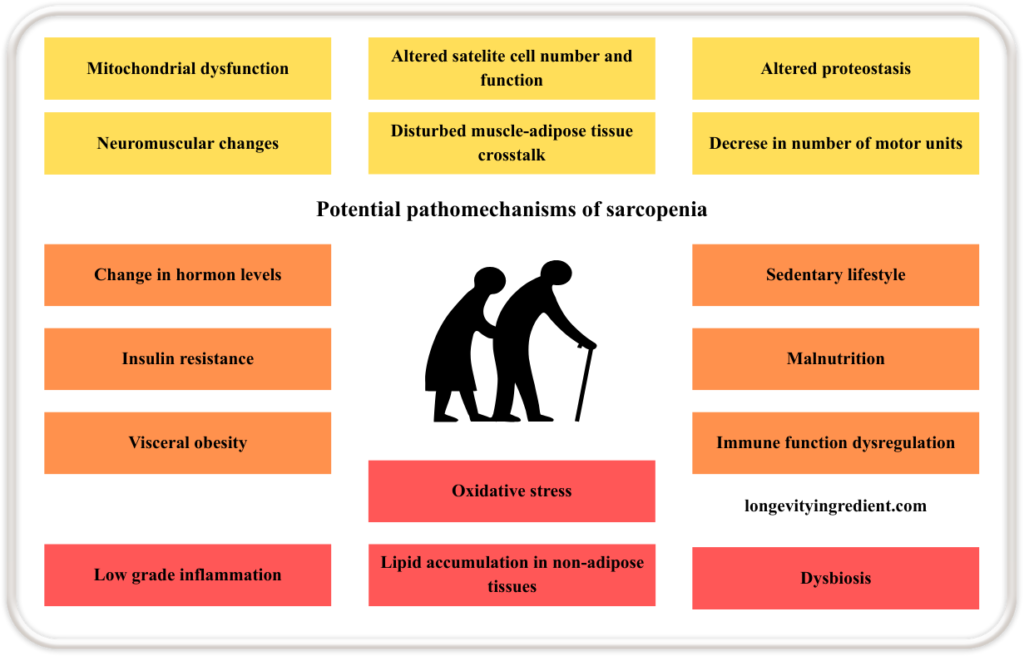

What’s the pathomechanism of sarcopenia?

Sarcopenia results from multiple interacting mechanisms. Starting from within the muscle itself: mitochondrial dysfunction, altered satellite cell number and function, impaired proteostasis (a process that regulates the balance of cellular production, folding, and degradation of proteins (Liang et al., 2023)), neuromuscular changes, disturbed communication between muscle and adipose tissue, and a reduced number of motor units.

All of the above contribute to the loss of muscle mass and strength. These are compounded by systemic factors such as changes in hormone levels, insulin resistance, visceral obesity, ectopic (in non-adipose tissues) lipid accumulation, oxidative stress, and dysbiosis of the gut microbiota. Lifestyle and immune-related influences, including a sedentary lifestyle, malnutrition, immune function dysregulation, and chronic low-grade inflammation, further accelerate the progression of sarcopenia (Fig.1) (Bilski et al., 2022).

Bone Density as a Marker of Ageing

Lower bone mineral density is associated with higher mortality risk across various populations, including elderly individuals, those with chronic diseases, and diabetes patients (Tsai et al., 2024).

The critical link between bone health and survival is largely explained by fracture risk and its consequences. When elderly individuals suffer hip fractures, the greatest danger isn’t the fracture itself, but rather the prolonged immobilisation that follows.

In nonagenarians (90+ years) with hip fractures, surgery dramatically improved survival – those who underwent surgery lived a median of 58 months compared to only 24 months for those who received non-operative treatment. The study shows that timing matters critically: patients who had surgery within 48 hours of admission survived significantly longer (median 73.8 months) than those operated on after 48 hours (39.7 months). Early surgery reduced immobilisation time, pneumonia rates, and overall mortality (Wang et al., 2024).

Maintaining bone health throughout life is essential because it helps prevent fractures and the life-threatening immobilisation that follows. At every age, movement is fundamental to survival.

The Link Between Menopause and Osteoporosis

Postmenopausal osteoporosis is a common condition affecting nearly 1 in 3 women. Estrogen deficiency, the primary driver of postmenopausal bone loss and osteoporosis, causes rapid bone loss, which peaks within the first 2–3 years after menopause (Gosset et al., 2021).

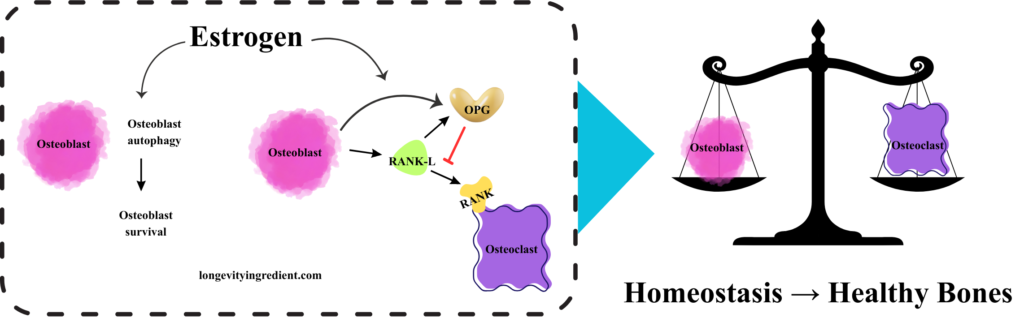

Let’s try to understand how estrogen deficiency drives bone loss, starting from the molecular mechanism by which estrogen maintains healthy bone homeostasis.

Healthy bones depend on a balance between osteoclast and osteoblast activity. Osteoclasts break down old or damaged bone, while osteoblasts form new bone and repair existing bone.

The left panel shows the cellular pathway where estrogen promotes bone health: osteoblasts (pink cells) undergo autophagy and survive in the presence of estrogen. These osteoblasts express two key proteins – OPG (osteoprotegerin, shown in yellow), which acts as a protective factor, and RANK-L (shown in green), which can stimulate bone resorption. OPG blocks RANK-L from activating the RANK receptor on osteoclasts (shown with a red inhibition line), preventing excessive osteoclast (purple cell) activity and thus preventing bone breakdown. The right panel depicts a classical balance scale with osteoblasts and osteoclasts perfectly balanced, symbolising homeostasis that supports healthy bones. This visualisation effectively shows how estrogen maintains balance between bone formation and bone resorption (Fig. 2).

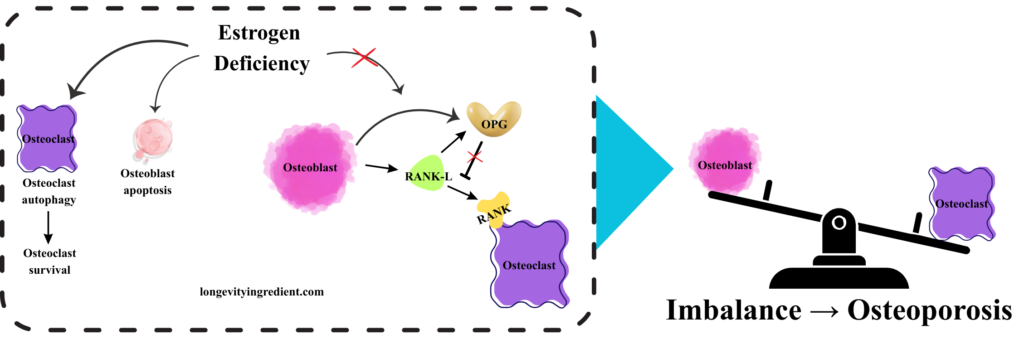

What happens when estrogen deficiency disrupts bone homeostasis? The left panel depicts the molecular cascade: osteoclasts (purple cells) survive through elevated autophagy, while osteoblasts (pink cells) undergo apoptosis rather than surviving. In this estrogen-deficient state, osteoblasts produce RANK-L (green), but OPG activity (yellow) is reduced. Without sufficient OPG to block it, RANK-L freely binds to and activates the RANK receptor on osteoclasts, triggering excessive bone resorption. The right panel shows a tilted balance scale – osteoclast activity now outweighs osteoblast activity, tipping heavily toward bone breakdown rather than formation (Fig. 3). This visualisation demonstrates how estrogen loss disrupts the delicate equilibrium shown in Figure 2, ultimately leading to osteoporosis through unchecked bone resorption.

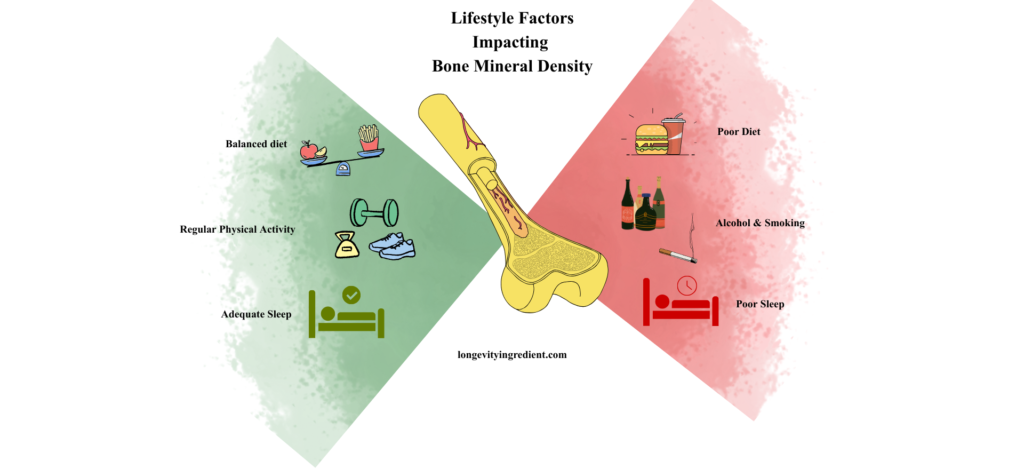

Estrogen deficiency isn’t the only threat. Other important risk factors include advanced age, genetics, smoking, low body weight, various diseases and medications that compromise bone health (McClung et al., 2021), heavy intake of alcohol, poor sleep and poor diet, meaning a high-calorie diet and/or insufficient nutrition (Fig. 4) (Hosein-Woodley et al., 2024).

The Key to Building Strong Muscles

While nutrition is crucial, it’s not the complete answer. Without physical activity, even the most optimal diet cannot prevent muscle loss.

As the ancient wisdom goes, “motion is lotion” – movement is essential for maintaining healthy muscles and bones. Physical exercise remains the key biological stimulus for bone-muscle crosstalk (Kirk et al., 2025).

The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends that adults aged 65 and older engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity weekly, plus muscle-strengthening activities on two or more days per week (Izquierdo et al., 2025).

Our improved understanding of sarcopenia mechanisms has enabled the development of combined dietary and physical activity approaches that can slow disease progression. These new strategies focus on optimising protein quality, quantity, and timing, alongside incorporating antioxidative nutrients.

To counter anabolic resistance, significantly increasing protein intake is essential. When simply increasing the amount proves insufficient, evenly distributing protein intake throughout the day shows promising results for muscle strength. The quality and variety of protein sources matter too – incorporating more plant-based proteins alongside animal proteins appears beneficial. However, since plant proteins have lower bioavailability, ensuring adequate total protein intake is crucial.

Vitamin D supplementation is recommended, given its dual role in both anabolic and antioxidative processes. Antioxidative dietary strategies should include fibres, vitamins, micronutrients, and polyphenols from diverse sources to support physical performance. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids positively influence body composition. Gut microbiota modifiers, particularly prebiotics, represent promising interventions for improving muscle mass, function, and body composition in sarcopenic patients.

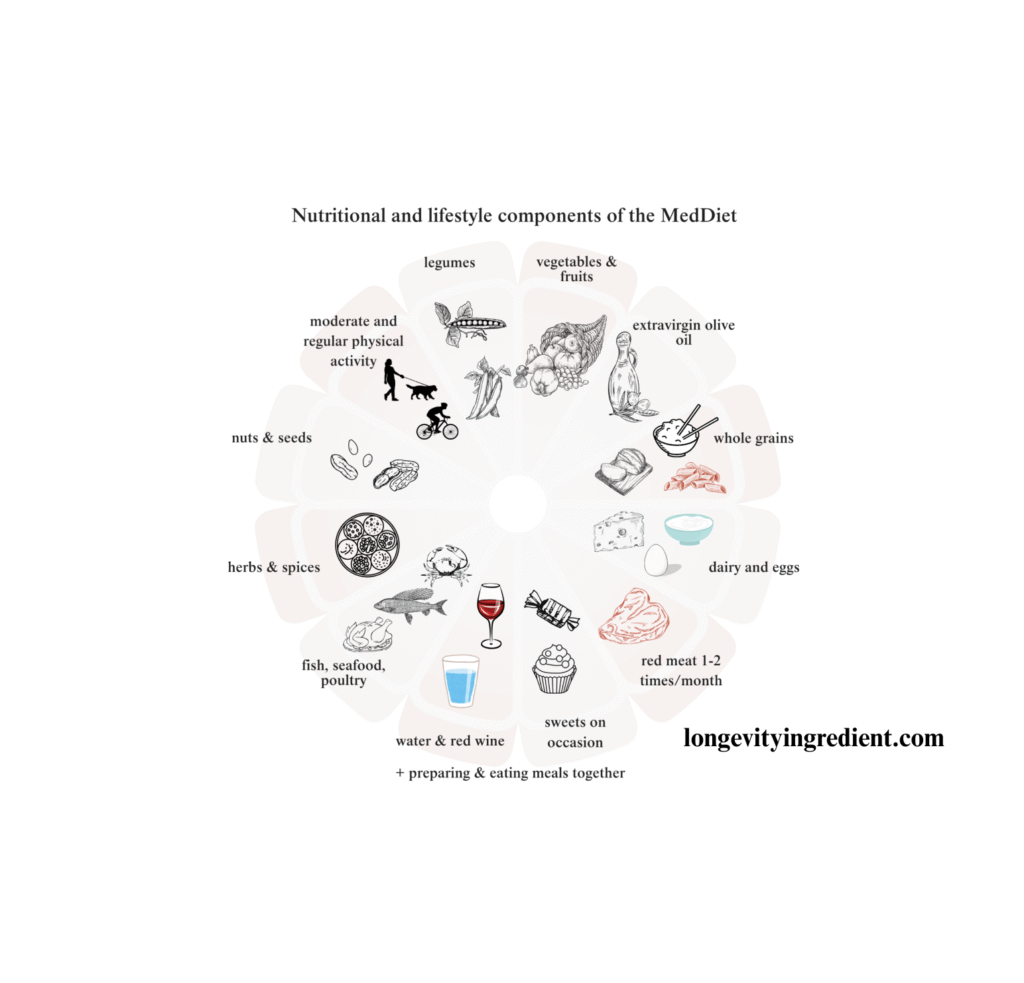

The combination of nutritional interventions with physical activity enhances outcomes in sarcopenia. For healthy older adults, adopting a Mediterranean-style diet represents one of the most effective lifestyle modifications. For individuals with sarcopenia where comprehensive lifestyle changes seem unlikely, targeted nutritional enrichment combined with physical activity offers valuable support in fighting sarcopenia (Cailleaux et al., 2024).

Evidence-Based Dietary Recommendations for Osteoporosis

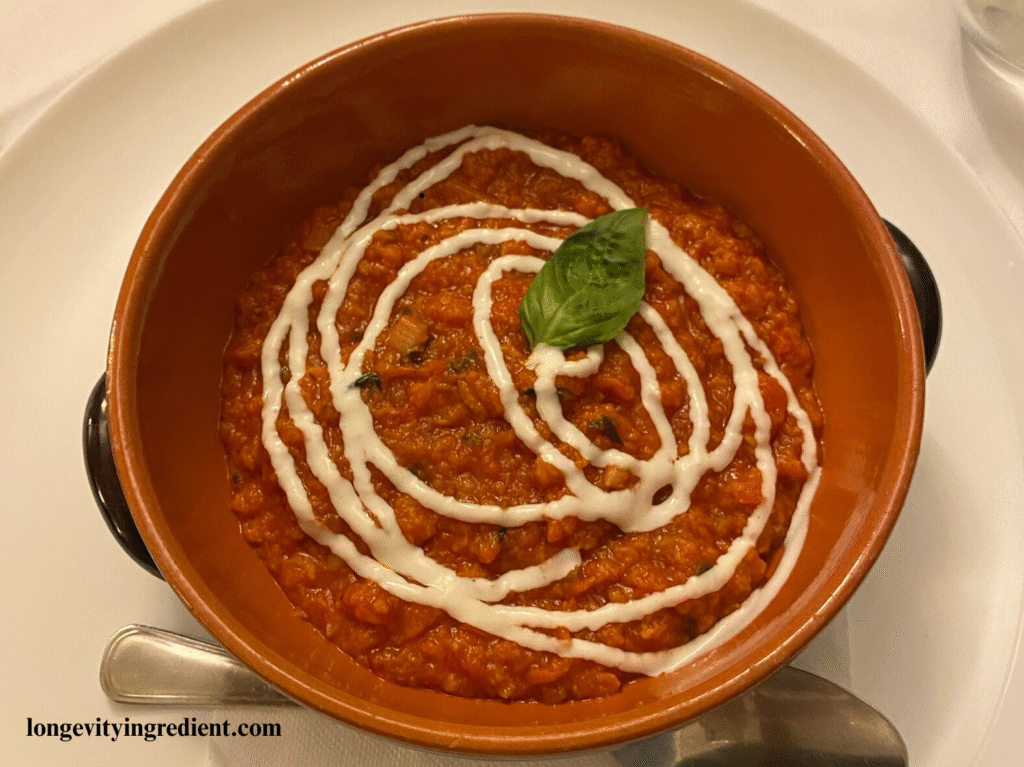

The Mediterranean diet has long been recognised for its health benefits. This traditional eating pattern emphasises vegetables, legumes, fruits, nuts, and whole grains, with olive oil as the primary fat source. It includes moderate amounts of fish, limited dairy products (mainly cheese and yoghurt), minimal meat and poultry, and moderate wine consumption with meals.

Research consistently demonstrates that Mediterranean dietary patterns support bone health. The combination of fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy products, and fish provides essential nutrients for maintaining strong bones (Quattrini et al., 2021).

The French Rheumatology Society and the Osteoporosis Research and Information Group have established comprehensive dietary guidelines for osteoporosis prevention and treatment. Their recommendations are based on current scientific evidence and provide practical guidance for maintaining bone health.

What to include

A Mediterranean-style diet combined with 2-3 daily servings of dairy products forms the foundation of bone-healthy nutrition.

This approach provides adequate calcium and high-quality protein necessary for maintaining calcium-phosphorus balance and healthy bone metabolism, while being associated with reduced fracture risk.

Protein intake deserves special attention. For individuals with osteoporosis or those focusing on prevention, aim for at least 1-1.2 g/kg of body weight daily (approximately 0.45-0.55 grams per pound). This should be part of a balanced diet with appropriate calcium and vitamin D intake. High-quality animal proteins are particularly beneficial, with dairy products offering the dual advantage of protein and calcium.

What to Avoid

Certain dietary patterns and habits can compromise bone health. Unbalanced Western diets, vegan diets, unnecessary weight-loss diets in individuals who aren’t overweight, excessive alcohol consumption, and daily soda consumption should be avoided.

Soda consumption particularly concerns bone health specialists. Regular soda intake not only affects bones directly but also often displaces healthier options like dairy products from the diet.

The Nuanced Picture: Tea, Coffee, and Supplements

Current evidence on some dietary components remains insufficient or conflicting. While high tea consumption may benefit bone health, the evidence isn’t strong enough to recommend increasing intake. Coffee consumption appears neutral – up to 3 cups daily shows no adverse effects on bones.

Regarding supplementation, vitamin D stands alone as the only vitamin with sufficient evidence supporting its use for bone health. Despite marketing claims, other vitamins, vitamin D-enriched foods, phytoestrogen-rich foods, calcium-enriched plant beverages, oral nutritional supplements, and prebiotic or probiotic foods lack convincing evidence for improving bone mineral density or reducing fracture risk (Biver et al., 2023).

Summary: Key Takeaways

What’s good for muscles is good for bones.

What to do: Engage in physical activity (ideally after consulting with a physiotherapist and doctor), follow a Mediterranean diet, consume 2–3 portions of dairy products daily, maintain optimal protein intake of 1–1.2g per kg of body weight (approximately 0.45–0.55 grams per pound) with appropriately adjusted calorie, calcium, and vitamin D intakes, and take vitamin D supplements.

What to avoid: Excessive phosphorus intake, alcohol consumption and smoking, soda consumption, excessive coffee consumption (more than 3 cups daily), and weight-loss diets in individuals who are not overweight.

Reference

Curtis E, Litwic A, Cooper C, Dennison E. Determinants of Muscle and Bone Aging. J Cell Physiol. 2015 Nov;230(11):2618-25. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25001. PMID: 25820482; PMCID: PMC4530476.

Mikel Izquierdo, Philipe de Souto Barreto, Hidenori Arai, Heike A. Bischoff-Ferrari, Eduardo L. Cadore, Matteo Cesari, Liang-Kung Chen, Paul M. Coen, Kerry S. Courneya, Gustavo Duque, Luigi Ferrucci, Roger A. Fielding, Antonio García-Hermoso, Luis Miguel Gutiérrez-Robledo, Stephen D.R. Harridge, Ben Kirk, Stephen Kritchevsky, Francesco Landi, Norman Lazarus, Teresa Liu-Ambrose, Emanuele Marzetti, Reshma A. Merchant, John E. Morley, Kaisu H. Pitkälä, Robinson Ramírez-Vélez, Leocadio Rodriguez-Mañas, Yves Rolland, Jorge G. Ruiz, Mikel L. Sáez de Asteasu, Dennis T. Villareal, Debra L. Waters, Chang Won Won, Bruno Vellas, Maria A. Fiatarone Singh, Global consensus on optimal exercise recommendations for enhancing healthy longevity in older adults (ICFSR), The Journal of nutrition, health and aging, Volume 29, Issue 1, 2025, 100401, ISSN 1279-7707, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnha.2024.100401.

McLeod M, Breen L, Hamilton DL, Philp A. Live strong and prosper: the importance of skeletal muscle strength for healthy ageing. Biogerontology. 2016 Jun;17(3):497-510. doi: 10.1007/s10522-015-9631-7. Epub 2016 Jan 20. PMID: 26791164; PMCID: PMC4889643.

Bilski J, Pierzchalski P, Szczepanik M, Bonior J, Zoladz JA. Multifactorial Mechanism of Sarcopenia and Sarcopenic Obesity. Role of Physical Exercise, Microbiota and Myokines. Cells. 2022; 11(1):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11010160

Rong Liang, Huabing Tan, Honglin Jin, Jincheng Wang, Zijian Tang, Xiaojie Lu, The tumour-promoting role of protein homeostasis: Implications for cancer immunotherapy, Cancer Letters, Volume 573, 2023, 216354, ISSN 0304-3835, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2023.216354.

Tsai YL, Chuang YC, Cheng YY, Deng YL, Lin SY, Hsu CS. Low Bone Mineral Density as a Predictor of Mortality and Infections in Stroke Patients: A Hospital-Based Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024 Nov 18;109(12):3055-3064. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgae365. PMID: 38795366.

Wang SH, Chang CW, Chai SW, Huang TS, Soong R, Lau NC, Chien CY. Surgical intervention may provides better outcomes for hip fracture in nonagenarian patients: A retrospective observational study. Heliyon. 2024 Jan 26;10(3):e25151. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e25151. PMID: 38322977; PMCID: PMC10844277.

Gosset A, Pouillès JM, Trémollieres F. Menopausal hormone therapy for the management of osteoporosis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021 Dec;35(6):101551. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2021.101551. Epub 2021 Jun 2. PMID: 34119418.

Michael R. McClung; JoAnn V. Pinkerton; Jennifer Blake; Felicia A. Cosman; E. Michael Lewiecki; Marla Shapiro; Management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: the 2021 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2021 Sep 1;28(9):973-997. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001831. PMID: 34448749.

Hosein-Woodley, Rasheed & Hirani, Rahim & Issani, Ali & Hussaini, Anum & Stala, Olivia & Smiley, Abbas & Etienne, Mill & Tiwari, Raj. (2024). Beyond the Surface: Uncovering Secondary Causes of Osteoporosis for Optimal Management. Biomedicines. 12. 2558. 10.3390/biomedicines12112558.

Kirk, B., Lombardi, G. & Duque, G. Bone and muscle crosstalk in ageing and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol 21, 375–390 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-025-01088-x

Cailleaux PE, Déchelotte P, Coëffier M. Novel dietary strategies to manage sarcopenia. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2024 May 1;27(3):234-243. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000001023. Epub 2024 Feb 23. PMID: 38391396.

Quattrini S, Pampaloni B, Gronchi G, Giusti F, Brandi ML. The Mediterranean Diet in Osteoporosis Prevention: An Insight in a Peri- and Post-Menopausal Population. Nutrients. 2021 Feb 6;13(2):531. doi: 10.3390/nu13020531. PMID: 33561997; PMCID: PMC7915719.

Emmanuel Biver, Julia Herrou, Guillaume Larid, Mélanie A. Legrand, Sara Gonnelli, Cédric Annweiler, Roland Chapurlat, Véronique Coxam, Patrice Fardellone, Thierry Thomas, Jean-Michel Lecerf, Bernard Cortet, Julien Paccou, Dietary recommendations in the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis, Joint Bone Spine, Volume 90, Issue 3, 2023, 105521, ISSN 1297-319X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2022.105521.