How to recognise an ultra-processed product?

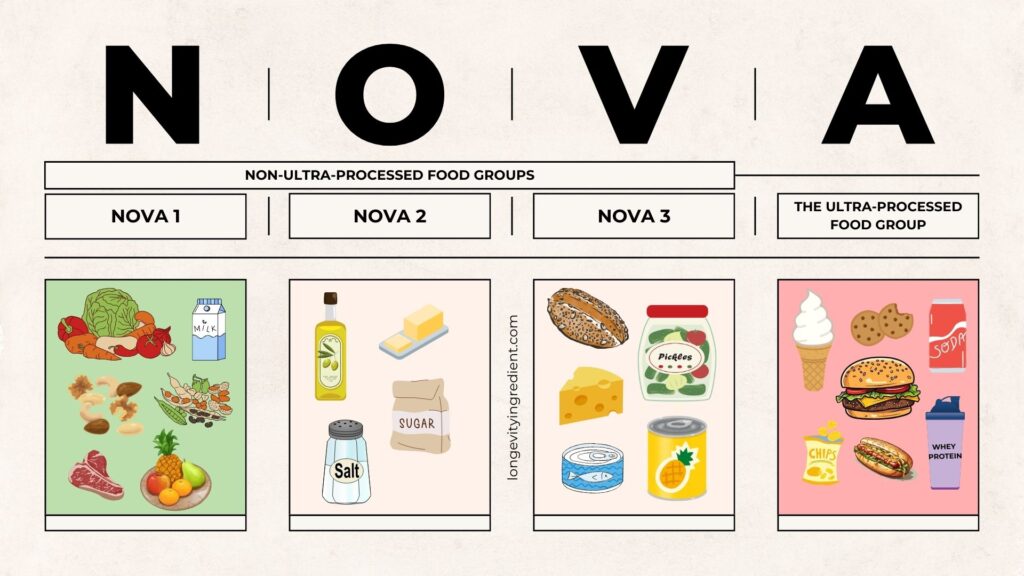

To identify ultra-processed products, let’s look at the NOVA classification system.

This classification divides foods into four groups based on the extent and purpose of industrial processing. A product’s classification depends on the physical, biological, and chemical methods used during manufacturing—including the addition of additives (Monterio et al., 2019).

Group 1 contains unprocessed or minimally processed foods—the edible parts of plants or animals taken directly from nature or minimally modified. Minimal processing includes removing inedible or unwanted parts, drying, crushing, grinding, fractioning, filtering, roasting, boiling, non-alcoholic fermentation, pasteurisation, refrigeration, chilling, freezing, placing in containers, and vacuum packaging. Examples include vegetables (e.g., vacuum-packed pre-boiled beetroot), fruit, nuts, milk, and fresh meat.

Group 2 contains processed culinary ingredients such as salt, sugar, oils, butter, or starch, produced from Group 1 foods. The processes include pressing, refining, centrifuging, milling, extracting, and drying. These ingredients are rarely or never consumed alone.

Group 3 contains processed foods made by combining Group 1 and Group 2 foods. This group includes products like freshly baked bread and cheese (made through non-alcoholic fermentation) and foods preserved by canning (e.g., canned fruit in syrup, canned fish) or bottling (e.g., vegetables in brine).

Group 4 contains ultra-processed foods (UPFs). These are no longer simply modified foods—they’re formulations made mostly or entirely from substances derived from foods and additives, with little to no intact Group 1 food. Products in this group typically have very long ingredient lists, are mostly ready-to-eat, highly palatable, and often inexpensive.

Examples include soft drinks, sweetened beverages, processed bread, refined breakfast cereals, confectionery (chocolate, cookies, candy, etc.), pre-packaged sauces, ready-to-heat meals (hot dogs, hamburgers, pizzas, etc.), processed meat products, infant formulas, follow-on milk, and other baby products.

Importantly, all “health” and “slimming” products—such as meal replacement shakes and powders, whey protein, and protein bars—also belong to this group (Fig.1) (Tristan-Asensi et al., 2023; Levy et al., 2024).

What is the impact of ultra-processed foods on health?

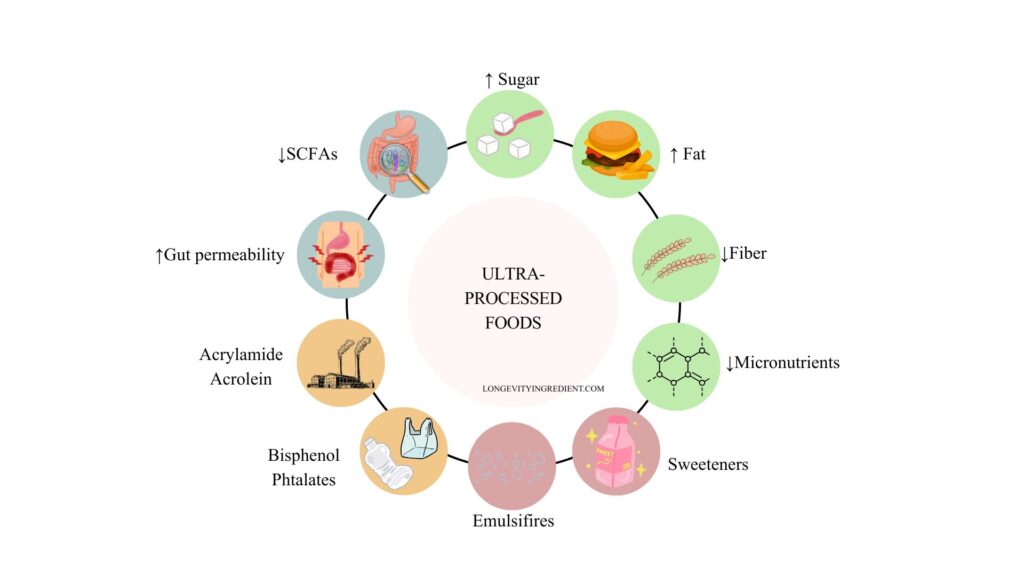

Ultra-processed foods pose serious health risks through multiple interconnected pathways. Nutritionally, they displace whole foods by delivering excess refined carbohydrates, saturated fats, added sugars, and sodium while being deficient in dietary fibre and micronutrients. The processing itself introduces elements such as: food additives like emulsifiers (e.g. carboxymethylcellulose, polysorbate-80), preservatives (e.g. sodium nitrates) and artificial sweeteners. Moreover, packaging leaches plastic molecules such as bisphenols and phthalates. High-heat processing generates toxic compounds, including acrolein and acrylamide (Fig.2). These elements are contributing to oxidative stress and insulin resistance (Tristan Asensi et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023).

Together, these factors create hyperpalatable, high-energy dense, potentially addictive foods that drive overconsumption, elevated glycemic response, low satiety, and increase the risk of metabolic dysfunction like obesity, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, cancer, and premature death (Monterio et al., 2019; Levy et al., 2024).

Ultra-processing destroys the food matrix and phytochemicals (natural chemicals produced by plants). Consuming these foods leads to increased gut permeability and inflammation while reducing the production of beneficial short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) (Fig.2) (Tristan Asensi et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023).

Key Findings on UPFs and Ageing

Dominguez et al. (2024) found that eating more ultra-processed foods is linked to being more frail.

But what does it mean to be frail?

“Frailty is a complex, age-related clinical condition that involves multiple contributing factors and raises the risk of adverse outcomes in older people.” (Dilma et al., 2024)

The researchers used the NOVA classification system to measure this. People who got more of their energy from UPFs had 1.02–3.22 times higher odds of frailty, even after accounting for confounders (variables that affect both the exposure and outcome, distorting their perceived relationship and potentially causing bias). Studies that followed people over time showed that getting 10–11% of your energy from UPFs over 3–3.5 years doubled the chance of frailty (Dominguez et al, 2024).

In 2025, Li et al. conducted a large study, called the Singapore Chinese Health Study, which involved 13,570 participants. They looked at UPF consumption in middle age and grip strength in old age. They found that people who ate more UPFs in middle age had weaker grip strength later in life, even when they accounted for overall diet quality. They measured grip strength with a device called a dynamometer and adjusted the results for age, lifestyle, health conditions, and diet quality.

Main results showed that people who ate the most UPFs had weaker grip strength: -0.411 kg compared to those who ate the least. When adjusted for height, it was -0.229 kg/m. The odds of having weak muscles were 1.32 times higher.

The researchers who conducted this study recommend eating fewer ultra-processed foods to help maintain muscle health as we age (Li et al., 2025).

But how about all of these ultra-processed healthy snacks?

There’s an important aspect of ultra-processed foods we need to consider: many of them fall under the category of “healthy snacks.” What about whey protein with low-calorie sweeteners, protein bars, and high-protein yoghurts with sweeteners?

Valicente and others (2023) asked a similar question in their article Ultraprocessed Foods and Obesity Risk: A Critical Review of Reported Mechanisms and made a compelling case. They reviewed mechanisms involving glycemic index, added sugars, fats, salt, low fibre, high energy density, and low-calorie sweeteners. In each case, the evidence does not support a special obesity-causing role for UPFs as a class. For example, high- versus low-GI diets, higher versus lower fat diets, higher fibre intake, and higher versus lower energy density show small or inconsistent effects on body weight. Meanwhile, low-calorie sweeteners—used as a UPF criterion—tend to modestly favour weight control when they replace sugar.

They note that “the claims about processing were stretched because the issue became more about formulation than processing, yet the claims did not evolve in step.” Importantly, the review showed that “UPF intake is neither sufficient nor necessary for weight gain and current effect sizes are modest.” And of course, it makes a lot of sense – you still need to eat more calories than you use during the day. This fundamental rule stays the same.

Valicente et al. make an interesting point about how UPFs provide food safety through long shelf life and deliver many nutrients, as these products are often enriched with vitamins and minerals. In fact, processed foods provide 50-91% of nutrients in European countries.

Here’s where the story takes a troubling turn: processed foods have become much cheaper than unprocessed foods in many countries. This leaves many people with no real choice. For the majority of society, regardless of income level, the cheaper option is simply more appealing. Only a very specific group of people will decide on food purely based on health benefits, regardless of the sometimes higher price.

This brings me to my own reflection: nothing is really black and white—not in nutrition, not in science in general. I agree that it seems unfair to put all ultra-processed foods in one basket and ask people not to consume them at all, when they represent the majority of foods available on the market.

The review’s overall conclusion: UPF intake is associated with higher BMI, but the NOVA-based claim that processing itself drives obesity is not backed by strong mechanistic evidence. Given potential downsides of blanket UPF avoidance—nutrient shortfalls, higher cost, lower food safety, more waste—the authors argue that policy should not rely on NOVA-style processing classifications alone. Instead, traditional principles of moderation, balance, and variety remain better supported by current science (Valicente et al., 2023).

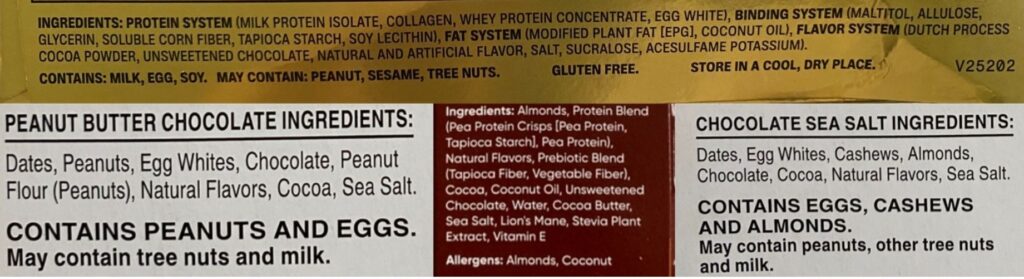

A case study of a few different healthy snacks from my pantry

I’m committed to avoiding sugar as much as possible in my daily life. Since I don’t eat many sweet things, when I crave something sweet, a piece of fruit or a homemade date-based snack easily satisfies me.

Nevertheless, I’m fascinated by the market for “healthy” snacks. I’m passionate about reading ingredient lists and trying products that seem innovative or minimally processed.

Lower-protein diets are less satiating and promote greater energy intake to meet protein needs, resulting in higher BMI. In contrast, high-protein diets supply protein needs with less energy and are associated with lower BMI. The strong satiety effects of higher protein intake are most consistently observed in solid foods. Therefore, high-protein energy bars—classified as UPFs—should theoretically benefit weight management. This contradicts the claim that UPF intake as a food class is problematic for weight management. However, most of these products are sugar-free and contain sweeteners, which aligns with evidence that low-calorie sweeteners tend to favour weight control modestly (Valicente et al., 2023).

Final thoughts

The evidence suggests we should generally minimise ultra-processed foods in our diet. However, the story isn’t quite so simple—there are shades of grey worth acknowledging.

Not all ultra-processed foods are created equal. An industrial pizza or hamburger shouldn’t be placed in the same category as a low-calorie, high-protein bar rich in fibre and amino acids. While it would be ideal to meet all our protein and fibre needs from whole, unprocessed foods, certain UPFs may serve a legitimate purpose.

The fundamental challenge with ultra-processed foods lies in the uncertainty: they contain numerous ingredients and additives whose long-term health impacts remain unclear. This is precisely why, as a precautionary approach, prioritising fresh, ultra-nutritious, home-cooked meals whenever possible makes sense for long-term health.

That said, I believe certain highly specific types of ultra-processed foods—particularly those that are low in sugar, high in protein, and nutrient-dense—don’t deserve to be heavily criticised or eliminated from the diet entirely. The key is discernment: understanding that while UPFs as a broad category warrant caution, there are exceptions that can support specific health goals without compromising overall well-being.

Reference

Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Levy RB, Moubarac JC, Louzada ML, Rauber F, Khandpur N, Cediel G, Neri D, Martinez-Steele E, Baraldi LG, Jaime PC. Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr. 2019 Apr;22(5):936-941. doi: 10.1017/S1368980018003762. Epub 2019 Feb 12. PMID: 30744710; PMCID: PMC10260459.

Tristan Asensi M, Napoletano A, Sofi F, Dinu M. Low-Grade Inflammation and Ultra-Processed Foods Consumption: A Review. Nutrients. 2023 Mar 22;15(6):1546. doi: 10.3390/nu15061546. PMID: 36986276; PMCID: PMC10058108.

Levy RB, Barata MF, Leite MA, Andrade GC. How and why ultra-processed foods harm human health. Proc Nutr Soc. 2024 Feb;83(1):1-8. doi: 10.1017/S0029665123003567. Epub 2023 Jul 10. PMID: 37424296.

Zhang Y, Giovannucci EL. Ultra-processed foods and health: a comprehensive review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2023;63(31):10836-10848. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2084359. Epub 2022 Jun 6. PMID: 35658669.

Valicente VM, Peng CH, Pacheco KN, Lin L, Kielb EI, Dawoodani E, Abdollahi A, Mattes RD. Ultraprocessed Foods and Obesity Risk: A Critical Review of Reported Mechanisms. Adv Nutr. 2023 Jul;14(4):718-738. doi: 10.1016/j.advnut.2023.04.006. Epub 2023 Apr 18. PMID: 37080461; PMCID: PMC10334162.

Dlima SD, Hall A, Aminu AQ, Akpan A, Todd C, Vardy ERLC. Frailty: a global health challenge in need of local action. BMJ Global Health. 2024;9:e015173. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2024-015173

Szumilas M. Explaining odds ratios. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010 Aug;19(3):227-9. Erratum in: J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015 Winter;24(1):58. PMID: 20842279; PMCID: PMC2938757.

Li Y, Chua KY, Pan A, Koh WP. Association between consumption of ultra-processed food at midlife and handgrip strength at late life: The Singapore Chinese Health Study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2025 Sep;29(9):100634. doi: 10.1016/j.jnha.2025.100634. Epub 2025 Jul 18. PMID: 40683211; PMCID: PMC12378926.

Be First to Comment